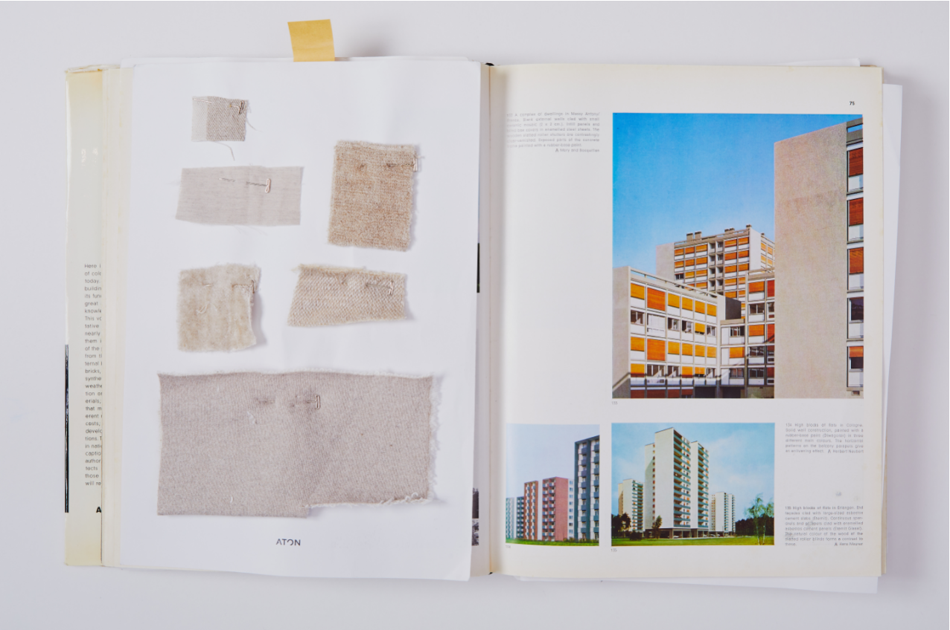

ATONCOLOR®

Spring/Summer 2025 Collection

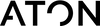

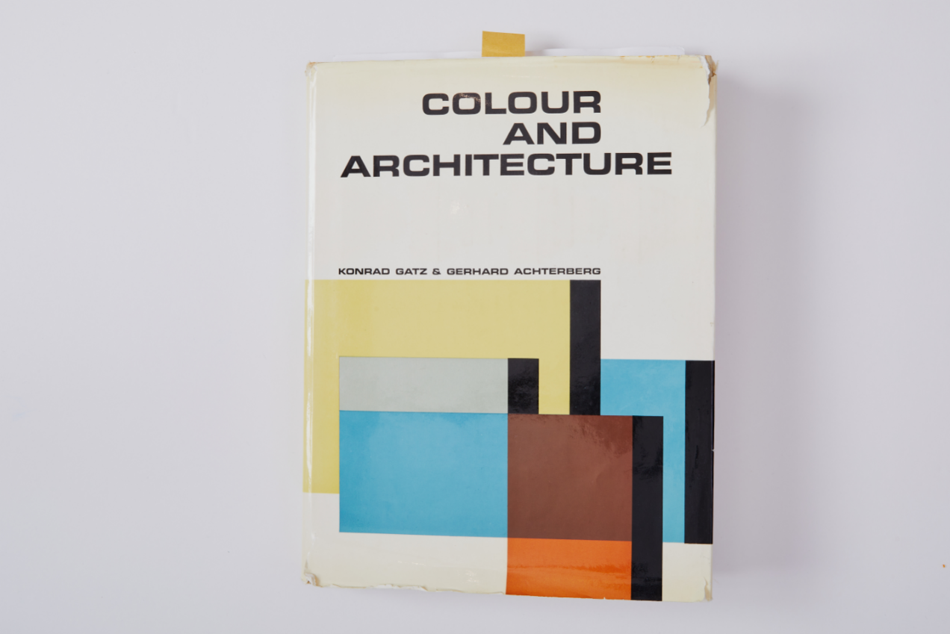

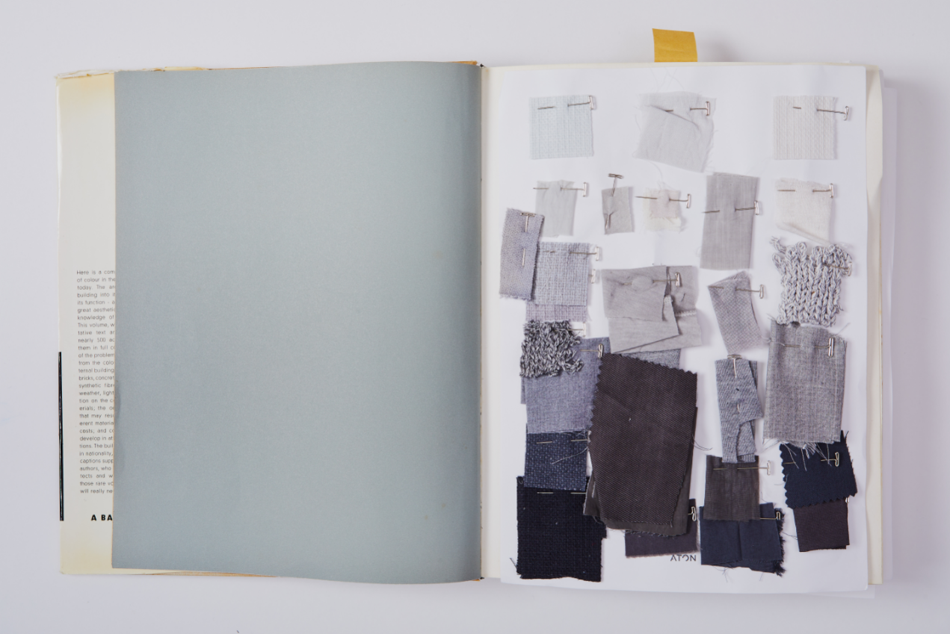

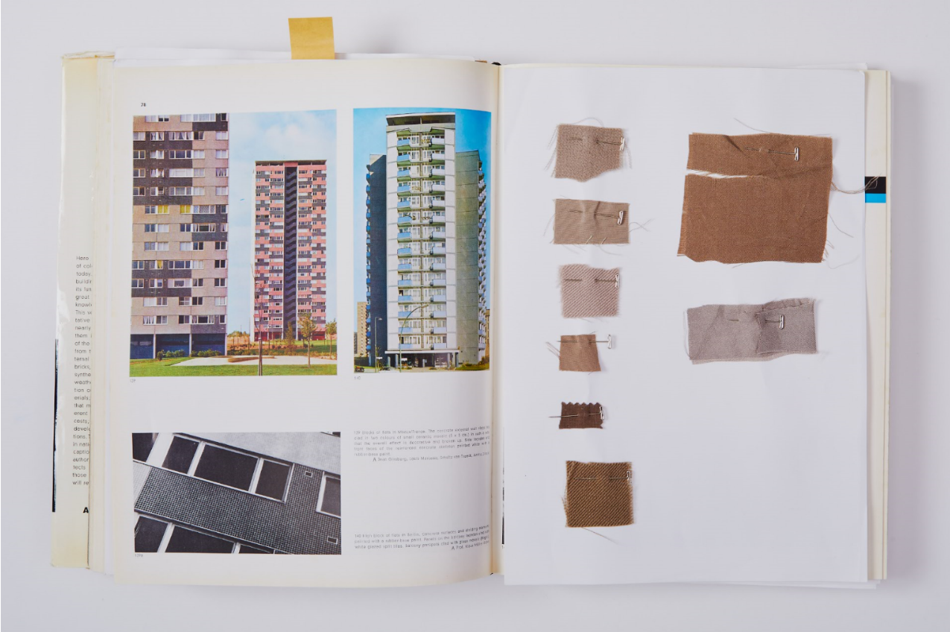

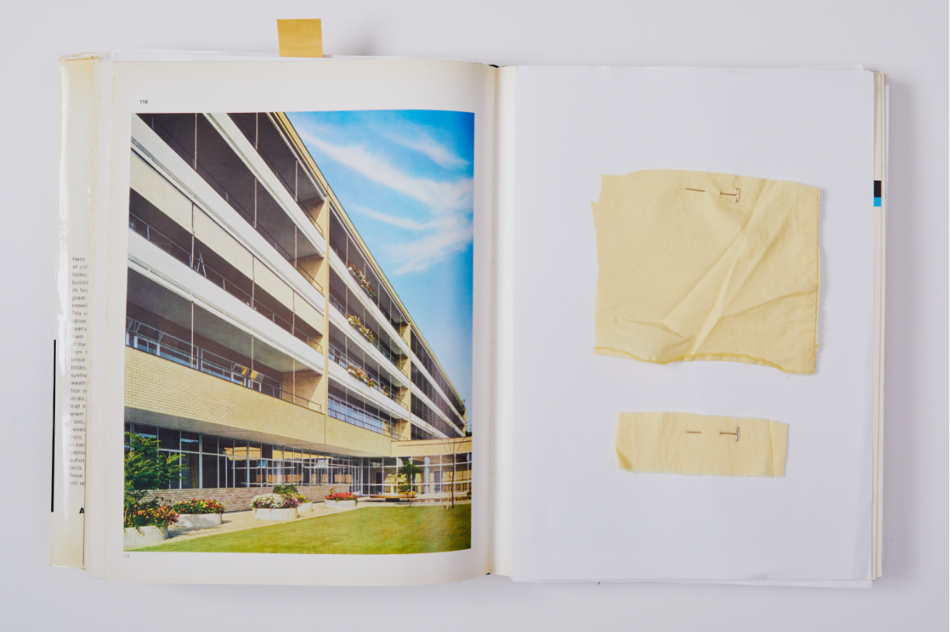

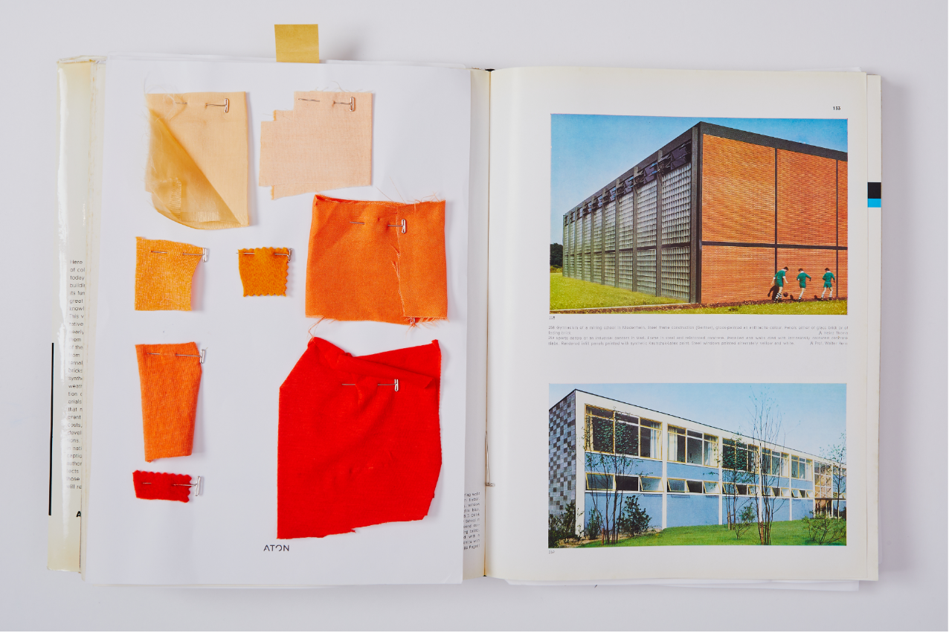

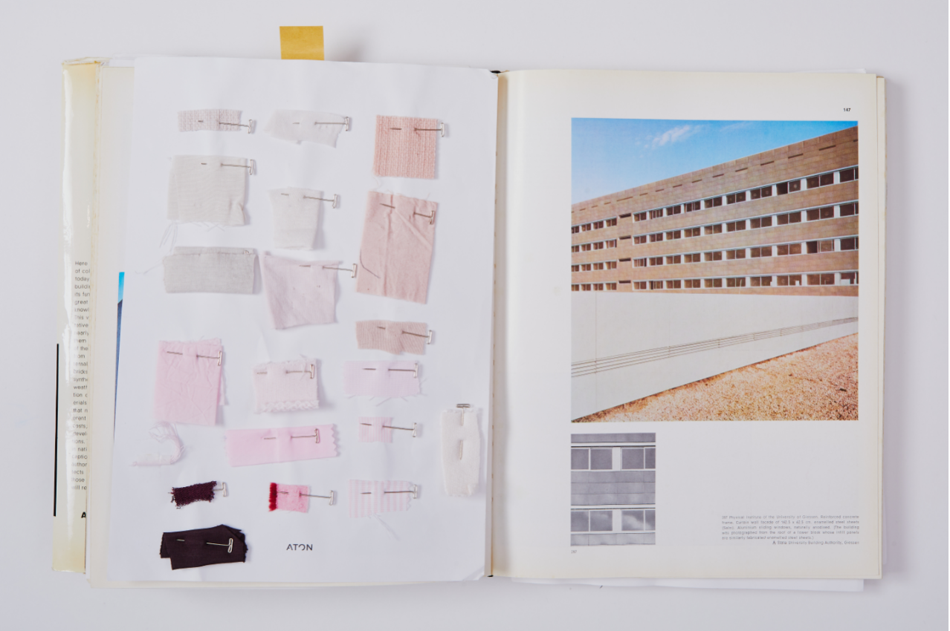

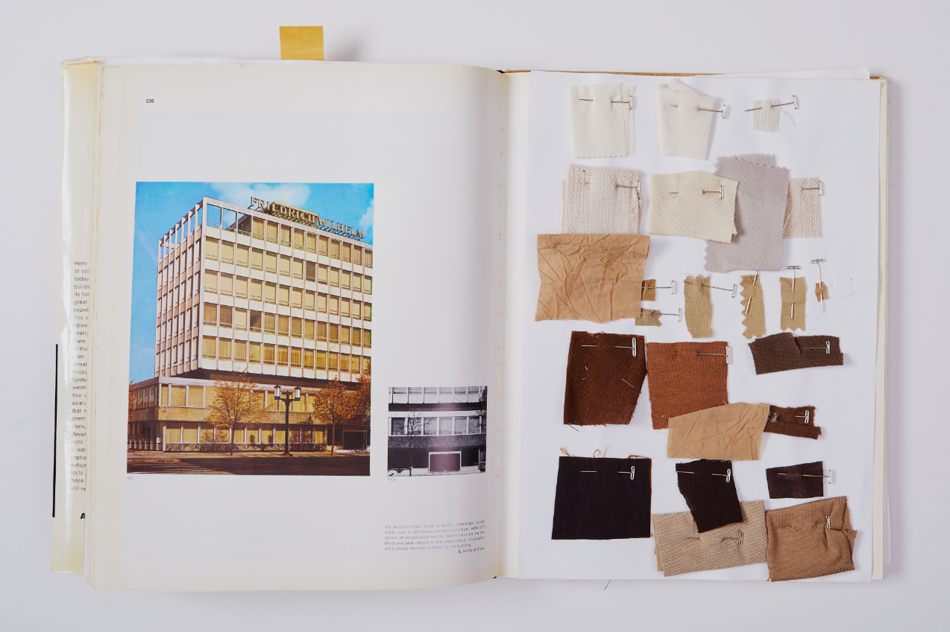

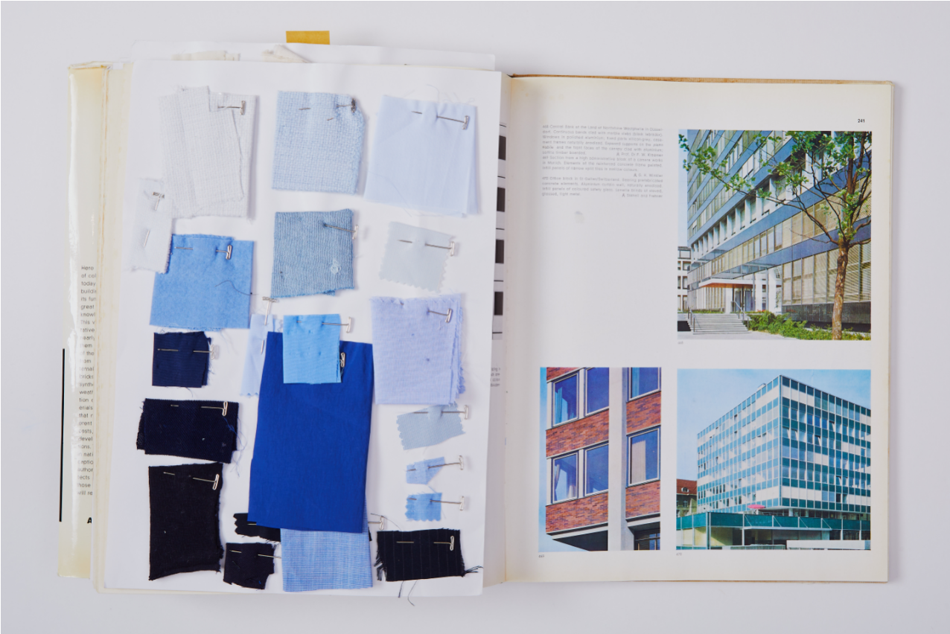

The colour imagery for this season was inspired by a German publication of architectural literature from the 1960s called COLOUR AND ARCHITECTURE. The shades of blocks and tiles used on the exteriors of the buildings in the book are beautifully coloured in light tones of beige, yellow, blue, green and pink. We focused on the faded tones created by the friction of rocks and stones washed away by the action of water in the country or region.

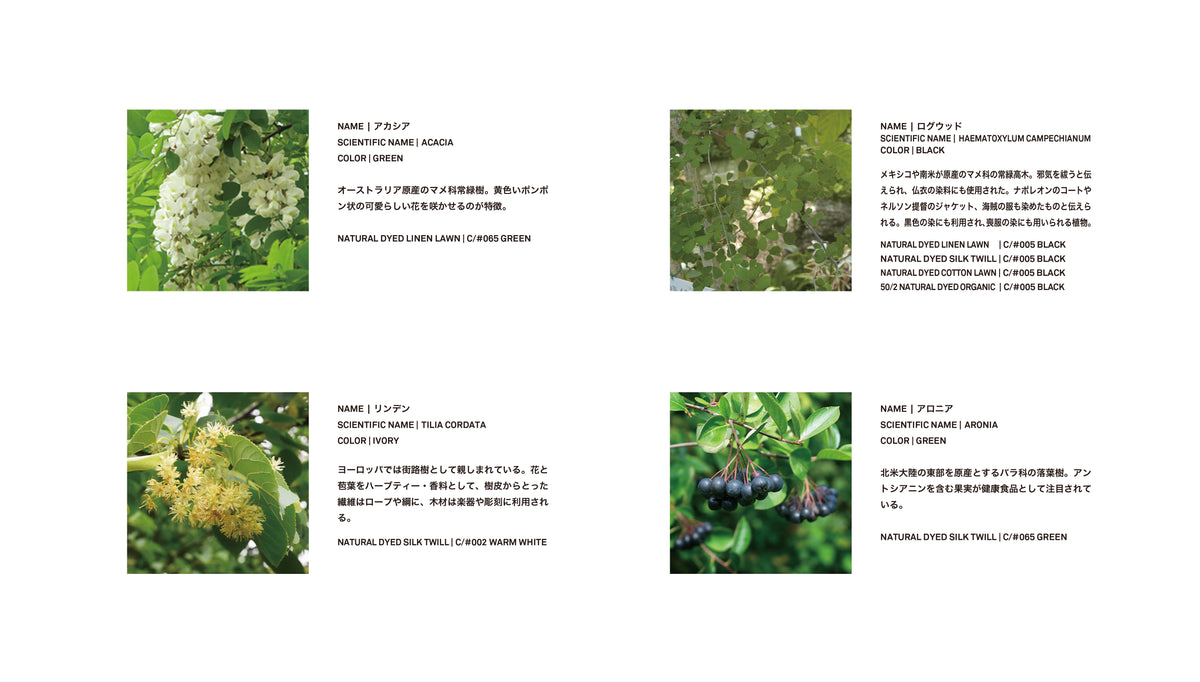

For the 2025SS ATONCOLOR®️, dyes are extracted from various plants growing in Germany to reflect the characteristics of the country or region.

ATON COLOR®

Our contemporary processes for making clothing all derive from techniques handed down from craftspeople that were refined over the ages. But our modern obsession with efficiency has caused us to neglect many splendid techniques of ntiquity, and little by little, they are being lost. And once lost, they can never be revived. That is precisely why ATON is working at the moment to preserve and evangelize small manufacturers and factories in Japan who continue to use rare and valuable production methods. We work closely with these craftsmen to try out new ideas and make beautiful clothes.

As just one example, let us look at dyeing techniques. Fabrics dyed with natural dyes possess a stunning depth of color, which we call botanical colors. These intricately layered colors are full of astounding beauty and have a unique ability to captivate the human senses at an almost primal level.

Botanical Dye

Natural colors are layered, which means they include wavelengths of light outside the range of human vision. Yet these “invisible colors” are critical for creating a depth of beauty. Keisuke Hishikawa, the founder of Cihon Tec in the Sendagaya neighborhood of Tokyo, came to this conclusion after 20 years of research into natural dyeing.

Even the most simple, standalone color is an expression of overlapping hues. This is why Hishikawa stocks 3,000 varieties of natural raw materials, such as leaves, stems, bark, fruit peels, ores, and the flowers of plants. He also maintains an archive of tens of thousands of dyes extracted from various natural raw materials, from the sakaki (Cleyera japonica) trees in the inner shrine of Ise Jingu to

the sasa broad-leaf bamboo of Mt. Omine in Nara Prefecture. Producing identical colors through multiple dyes of natural materials is extremely difficult, but Cihon Tec can achieve the same colors each time thanks to digitizing its recipes.

Indigo

Traditionally it was prohibited for craftsmen to take Ryukyu indigo out of Okinawa. The first person allowed to do so was the late Yuzen craftsmen, Keiichi Yoshikawa, who brought Ryukyu indigo to Kyoto after repeated training in Okinawa. The resulting Ryukyu indigo feels very modern, much different than that produced in Okinawa, thanks to the purity of Kyoto water. (Kyoto has even been called “the city above a water jug.”)

To make indigo dye, craftsmen extract a solution from the fermentation of naturally dried indigo leaves. They call this process "building the indigo," once it takes on a reddish foam known as "indigo flowers," it’s ready for hand-dyeing garments. When fabrics

first emerge from the dye, they take on a yellow tint, but once oxidized in the air, they transform into their signature blue color. By varying the number of dips into the dye, 48 separate shades of indigo can be created: kamenozoki "pot peering” light blue, mizuiro light blue, hanada purple-blue, onando dark cyan, ai indigo, tetsukon navy blue, and katsuiro deep blue. By using Mr. Yoshikawa’s techniques, craftsmen in Kameoka, Kyoto continue to dye indigo by hand and convey the beauty of Ryukyu indigo in each piece.

Logwood

In the past, the only available material for black dye was logwood. It was used, for example, to produce the black in Napoleon’s legendary wool coat. This rare Mexican tree was so in demand that wars even broke out over access to it.

To dye things black with logwood while preserving the firmness and luster of high-density woven linen requires a primitive technique called jigger dyeing. There is a factory for jigger dyeing in Hanyū, Saitama Prefecture that has been operating continuously for 140 years.

The factory wraps linen cloth around a roller and then rotates that around another roller to let it pass through dyeing liquid extracted from the logwood. After the first winding, the cloth is rotated in the reverse direction and again rolled through the dyeing solution. Since the dyeing occurs while the fabric is stretched out, the fabric takes on a glossiness and luster that cannot be obtained by other dyeing methods, such as rubbing in the color. Black may appear to be monochromatic, but garments only become black from emitting a wide variety of colors through the reflection of light.

Anthurium

Anthurium is an herb found in the area between the tropical regions of America and the West Indies. The reddish leaves, called butsuenhō, which wrap the buds like petals, produce a red dye that turns fabric a bright pale pink.

We dye sweatshirts in anthurium, but doing this without damaging the thickness and density of the cotton fabric requires a technique called paddle dyeing. In Koishikawa, Tokyo, there is a dyeing factory that has practiced paddle dyeing for nearly 110 years. Here the sweatshirts are dyed as if they are swimming in the dye. The fabric never touches the machine directly, nor rubs against other fabric, which is key to preserving the texture of the fabric. When dyeing finished garments, there is no unevenness in the color, even in areas near the stitches, which makes it look like they were sewn from pre-dyed fabric.

The sweatshirts are dried naturally without using an industrial dryer, which ensures the integrity of the thick cotton fabric.